Norwegian and Nigerian Woods: Keziah Jones and the Beatles

At the beginning of the title song of Keziah Jones’ masterpiece Nigerian Wood, an Oxbridgy voice tells us we are about to hear “African music research, long playing record, side two,” and that we’ll open up with a “a dance song with a moral.” The joke is, of course, that we are about to hear a CD of modern dance music produced by an African who delivers it to us himself, ostensibly unshepherded by any form of ethnographic mediation. And sampling Dr. Oxbridge (as he was in the act of sampling some tribal savages dancing and howling) is the postcolonial turnabout move par excellence, an assertion of cultural self-possession via the rhetoric of signifyin’ mimicry. But since Bhabha and Gates are no longer as cutting edge as they once were, I’m less interested in the fact of signifyin’ mimicry than I am in what is being signified, and in Jones’ own commentary on what he’s doing. After all, while he is clearly mocking the speaker, Dr. Oxbridge’s statement is also completely true on the most basic literal level: this is dance music, become the vehicle for social commentary. But in this case, its commentary is addressed to exactly this process, to the ways that Jones’ own music functions as a cultural commodity, and about the ways that the production of cultural texts (like this very song) gets commodified and marketed.

“You want the best Mahogany…Designed to keep you company Memories…Through all safari memories…You want the best Mahogany”

Those are the opening lines. Most obviously it’s a play on “Norwegian Wood,” a song you may have heard by some band from Liverpool, one of the most important ports of origin where 19th century slave ships and capital set sail for West Africa. But the “wood” which Jones is singing about isn’t merely a particular commodity that comes from Africa. Instead, the fact that the album is itself named “Nigerian Wood” makes these references intensely self-referential: like its creator, nee Olufemi Sanyaolu of Nigeria, now Keziah Jones of London, the album is itself a commodity come from Africa to England, and a commodity whose value derives, in part, from exactly the manner in which it has been set into circulation as a thing from elsewhere, a piece of “world music” (the Beatles, of course, were not from this world). Just as commodities acquire value by being transported from a place where they are plentiful/unwanted to a place where they are rare/desirable, so too does “world music” attach value to music (like Jones’) in places where it is desirable as a function of its rarity.

“Oh colonies…Guess what we brought from the colonies Ebony….No Ivory, just Ebony…Oh, Mahogany… Bone is from China [indecipherable] Guess what we brought from the colonies”

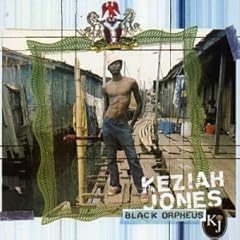

Keziah Jones understands this, I think, or at least his song acts like he does. And since the African-ness of black music has so often been treated as a function of its “hot” sexuality (see, for example, this Radano piece Wayne turned me on to), it is hardly surprising that his references to Nigerian “Wood” are exactly as hyper-sexualized as African music is  constantly taken to be (albeit knowingly). He’s good at living up to that particular expectation; as a performer known for his impressively shirtless physique (as in this youtube clip) I think we are safe in assuming that when he sings lines like “Open those gates for ebony,” “Gotta have wood that’s good,” and “Nigerian timber is what you need,” he is pretty much talking about his penis. Not to point too fine a point on it. Or, rather, an allusion to the historical process by which African bodies were converted into global commodities and sold has become a kind of metaphor for the thing he is now doing: transforming his body into a commodity and selling it. And like Dr. Oxbridge, I think, what is most interesting about it all is that it’s both intensely ironic and completely sincere, both a self-conscious highlighting of the desire to commodify cultural difference and, simultaneously, a full voiced performance of that desire.

constantly taken to be (albeit knowingly). He’s good at living up to that particular expectation; as a performer known for his impressively shirtless physique (as in this youtube clip) I think we are safe in assuming that when he sings lines like “Open those gates for ebony,” “Gotta have wood that’s good,” and “Nigerian timber is what you need,” he is pretty much talking about his penis. Not to point too fine a point on it. Or, rather, an allusion to the historical process by which African bodies were converted into global commodities and sold has become a kind of metaphor for the thing he is now doing: transforming his body into a commodity and selling it. And like Dr. Oxbridge, I think, what is most interesting about it all is that it’s both intensely ironic and completely sincere, both a self-conscious highlighting of the desire to commodify cultural difference and, simultaneously, a full voiced performance of that desire.

“Nigerian Wood Beatles never understood Gotta have wood that’s good, yeah For Nigerian Wood”

I wonder what he thinks the Beatles never understood. Other than the sly pun on wood-boring beetles, perhaps the fact that “Norwegian Wood” was itself built on an Irish fiddle melody even has something to do with it, as an example of the way popular music appeals to racializations we might not even register as such, melodies and instrumental arrangements that we feel as having particular racial or national connotations, but which we then studiously unspeak. I’m thinking of the way “Norwegian Wood” feels Irish without having to admit that it is, or the way a particular melody can sound “oriental” or “tribal” or “hillbilly” without having to explicitly admit that that’s what it’s doing. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course; popular music is all about stealing from and then forgetting your sources, even if copyright lawyers might remember to forget that as well. And there’s no reason, necessarily, why Lennon had to acknowledge the implicit Irishness of that kind of melody, no reason why he had to make the song about that. I like the fact that it’s a song about failing to get laid and then burning down the house of the “bird” in question, and I’m not asking it to be a different song than that.

“Oak is amazing, Teak is unique Nigerian Timber is what you need Oak is amazing, Teak is unique Nigerian Timber is what you need”

But while the Beatles were nowhere near as crass as, say, Led Zeppelin in stealing from Black American musicians – nor anything like as derivative of their source texts anyway – there is still a kind of amnesia about those sources that runs through their music, and through rock n’ roll in general, and maybe this is what makes Jones’ lyrics what they are. It’s sort of emblematic that the very word went from being a slang term for sex affiliated with “race” music to being a de-sexualized and de-racialized formal category, pretty much by virtue of leaving the hands of the black musians who coined it and becoming the provenance of white “Rockers.” Plus, did the Beatles ever really write about sex? They wrote about it all the time, in a way, but rarely admitted it; “She was just seventeen, and you know what I mean,” for example, is an exemplary early lyric, but that sort of coy unspoken reference is far more typical than anything as straightforward as Nigerian Wood. Most of the time it wasn’t sex, but “love,” and when it wasn’t that airy reference to the unspeakable, it was speaking as unspeakable, sex as obscenity (as when they chant “tit-tit-tit” in “Girl” or use obscure Liverpudlian slang like “for a fish and finger pie” in “Penny Lane”).

“I once had a girl, or should I say, she once had me She showed me her room, isn’t it good, Norwegian Wood”

It would be easy, too, to be flip and note how intensely “white” a song is that that transfers desire for sex into a zest for interior decorating. And once you start down this path, it’s hard to stop: go ahead, John Lennon, sleep in the bath, try to scrape the sex off that song. But it’s also hard not to notice, as you do it, that the singer’s inability to act on his desires – sublating them into violence – nicely rhymes with the ostentatious over-euphemism of the lyrics themselves. And maybe that’s Lennon’s point. Norwegian “Wood” indeed…